Previously, GameFi meant primitive farms with NFT pictures.

In 2025, it is a full-fledged niche on different blockchains with seasonal economies, guilds, and a developed in-game market.

In this article we’ll explain

• What GameFi and P2E are

• How this niche emerged

• Which categories of projects exist

• The pros and cons of the sector

• Why venture funds still keep putting money into it

What are GameFi and P2E?

GameFi — are games with a built-in crypto economy.

The user performs in-game actions: gathers resources, fights mobs, completes various quests, and levels up their characters. In return, the player receives digital assets that really belong to them on-chain, since games most often use non-custodial wallets (what is a non-custodial wallet?), rather than being stored on the servers of the game developer.

Play-to-Earn (P2E) — is a model in which game progress is converted into value.

Rewards can be different: in-game tokens, items, characters. Items and characters can also be tokenized as NFT (what is an NFT?).

All of this is transferred and stored on the blockchain, which means the player can sell it to another person, withdraw it to an exchange, or swap it for stablecoins or the project’s token.

This is the same gaming experience, just with a transparent economy and actual ownership of assets.

Brief history of GameFi

Roughly speaking, we can distinguish three stages of development.

Early experiments

Back in the early 2010s, some projects experimented with accepting bitcoin as a currency, and third-party plugins appeared in Minecraft that allowed cryptocurrencies to be connected to in-game mechanics.

The first wave — NFT and CryptoKitties

In 2017, the game CryptoKitties was released — a game where users bred unique digital cats. The project showed that in-game items can be unique NFTs and that players are willing to pay for ownership. Prices for rare cats were rising, the Ethereum network was periodically crashing under the load, and it was exactly this period that laid the foundation for GameFi.

The explosion of Play-to-Earn in 2020–2021

Axie Infinity and other P2E projects became global phenomena. For the first time, users were earning “game income”. Soon it turned out that the economies of early projects were overly dependent on a constant influx of new people, rewards were being devalued, the model needed a redesign, and everything was turning into a Ponzi scheme.

Maturity stage — GameFi

From 2023–2025, projects began to appear that aim to be a game first and only then a financial model. Farming seasons, limited resources, token burns, in-game “taxes”, guilds, asset renting, and different player roles emerged. Developers abandoned endless reward farming and moved toward more balanced and thought-out economic systems.

Categories of GameFi projects

P2E and play-and-Own

Games where you receive tokens and in-game items simply for participating. This is the familiar format: grind, progression, quests, PvP, ranks.

In Play-and-Own the emphasis is on the player owning the items, even if the economic component is not dominant.

Free-to-Play GameFi

Games you can enter for free. This model has become an important counterbalance to expensive NFT entry tickets. Newcomers can explore the world without investing money and only later decide whether it’s worth moving on to paid activities.

Metaverses and sandboxes

Projects in which users own land, buildings, create their own locations, mini-games, and events.

The mechanics are similar to traditional sandbox games, but with ownership verified via blockchain.

Move-to-Earn andother X-to-Earn

Projects where the player has to perform actions in the real world.

The first M2E waves were explosive. A good example is STEPN, but the effect was short-lived: the model quickly burned out due to overinflated expectations, weak economics, and lack of new content. Today it is a dead format.

Pros and cons of GameFi

Pros

The main advantage is that the player owns their progress. Valuable items can be sold or transferred. In some projects, earnings can indeed be significant, especially when it comes to seasonal tournaments, prize pools, or the early stages of a project.

Cons

The economies are unstable. Token prices can fall many times over simply due to market cycles. Many projects look promising only on paper and in practice fail to withstand competitive pressure.

Sector metrics: what is happening in 2025

GameFi remains a relatively small sector by market cap compared to memecoins or the AI narrative. At the same time, GameFI is among the most actively developing Web3 segments.

The total GameFi market is estimated at around $20.3 billion;

Venture investments have decreased significantly but have not disappeared completely, with funds becoming more selective.

Why venture funds continue to invest in GameFi

Despite the failures of the first waves, funds understand that gaming is one of the largest entertainment markets in the world.

If Web3 secures even a small share of this segment, the revenue will be quite significant.

Funds are betting not on quick profits, but on the long game.

But we’re not here to wait years for profits.

The Notcoin phenomenon and the «death» of tap-to-earn

The Notcoin project became one of the most viral game mechanics. A simple Telegram bot where you literally had to tap on a coin attracted millions of users.

The project became a precedent: many people saw for the first time how a game could bring profit with zero spending.

But then the tap-to-earn sector drowned in clones. The mechanic was too simple, too easy to copy, and it saturated the market too quickly. There wasn’t enough liquidity for the number of users that had been attracted to the TON network.

The narrative burned out in just a couple of months and collapsed.

This example highlights that gaming projects, despite exceptions, are most often a quick entry, earnings, and a “took the money, sold, left” strategy.

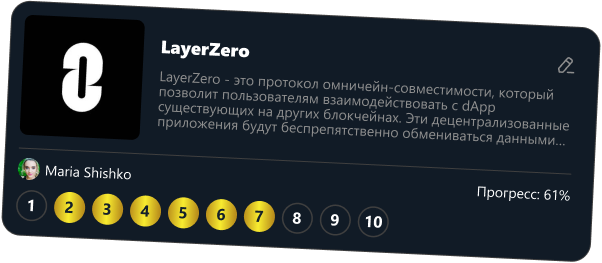

There is an exception. Cambria is an MMORPG in a blockchain environment:

The player leaves the safe zone, gathers resources, kills mobs, searches chests, and finds valuable loot.

After the run, they return to the city and turn in their spoils. This grants two types of progress:

- In-game currency that affects the final share in the prize pool;

- Influence points that convert into progress towards a future airdrop.

The character has energy. Actions in dangerous zones consume it.

There is a free progression option, but you should understand that it won’t yield a large drop: you’ll have to play in small sessions, carefully saving energy.

There is also a paid option: buying restorative items and grinding in long sessions.

The longer the character stays in the dangerous zone, the higher the chance of rare loot, but also the higher the risk of losing everything upon death. This raises strategic questions: how long to stay, when to turn back, which zones to choose, and how much you’re willing to invest in working the project out.

At any moment the player can encounter other players and lose their items. This creates pressure and makes the economy dynamic. Rewards are tied, among other things, to risk management.

In Cambria the third season is already launching, and the project will successfully complete it, rewarding active users.

Conclusions:

GameFi — is not an attempt to replace work with games or a way to “earn money by doing nothing”. It is a sector where game mechanics, economic models, risk management, and market demand intersect.

The development of the sector goes in waves: from the hype P2E of 2021 to seasonal economies and infrastructural airdrop mechanics of 2025.

Some directions have burned out, like tap-to-earn, while others are only gaining momentum.

At the start, it’s important to understand a simple thing: GameFi is not guaranteed income, but an experimental game economy where you can both earn and lose your investment.

To feel more confident, it’s worth starting with free modes, studying the mechanics, looking at on-chain metrics, and only then making decisions.